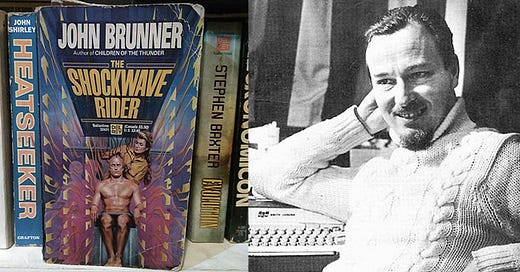

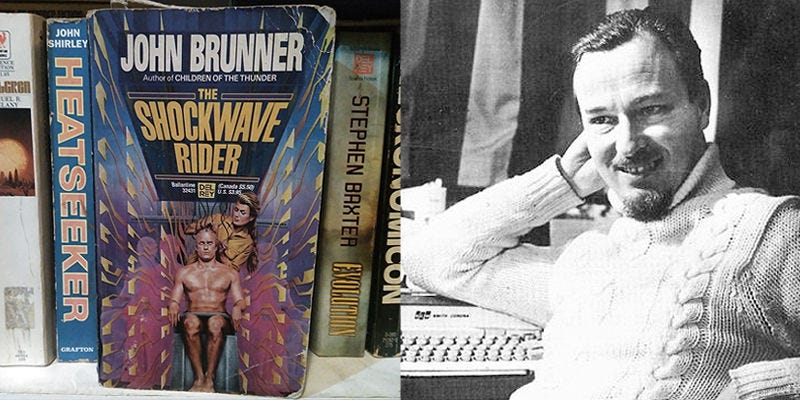

This Writer Could Have Been The Next Heinlein According To One Of Sci-Fi's Most Famous Editors

John Brunner had the chance to become the next big name in science fiction, but he disappeared for a lot of years, slowing his career and eventually bringing it to a halt before his death. What happened was a tragedy of timing, as with so many authors, where the writing business didn’t align with his life events.

Most science fiction fans know the name …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Fandom Pulse to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.