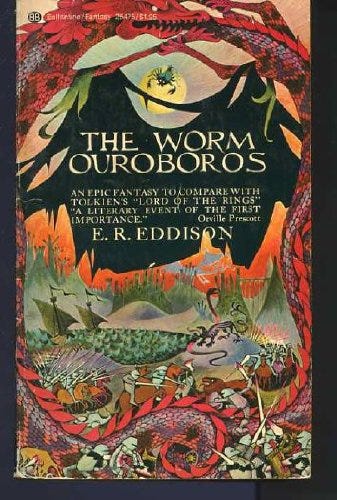

Imagine a fantasy epic where war has no end, victory feels hollow, and the words themselves cast a spell. Welcome to E.R. Eddison’s The Worm Ouroboros (1922). It’s a novel so unapologetically grand it still dares modern readers to keep up. Overshadowed by Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, published two decades later, Eddison’s saga of Demonland’s endless war with Witchland stands as a breathtaking testament to eternal struggle, moral ambiguity, and the raw power of mythic storytelling.

Why should you care about a 1920s fantasy with archaic prose? Because The Worm Ouroboros delivers an unflinching vision of heroism and beauty. It is honest, uncompromising, and unlike the avalanche of derivative paperback fantasies that followed.

A Work of Daring Imagination

James Stephens, one of Eddison’s earliest champions, wrote in The Irish Statesman that the novel is “a wonderful book” filled with mythic energy that soars “where lightning is the norm of speed.”[i] Decades later, Donald Barr, writing for The New York Times Book Review, hailed it as a “world of Ought-to-Be,” a realm where ultimate values are revealed through fearless action.[ii]

Long before Middle-earth existed, Eddison crafted a fully self-contained fantasy world. In a 1957 letter, Tolkien described Eddison as “the greatest and most convincing writer of invented worlds.”[iii] Although he clarified that same letter Eddison was not an influence. Ouch!

Brian Stableford, in Survey of Modern Fantasy Literature, credits Eddison with pioneering tropes we now take for granted: enchanted towers, grand quests, beasts debating philosophy with heroes, and so on.[iv] Eugene Larson, writing for the Critical Survey of Science Fiction and Fantasy Literature, saw the novel as a bridge from William Morris’s romantic fantasies to Tolkien’s epic.[v] Joseph Young, in a 2013 issue of Extrapolation, argues Eddison’s style was shaped not by medieval texts Eddison endeavoured to translate, but by childhood daydreams. Those dreams giving his imagined world a wildness Tolkien’s more structured invention rarely matched.[vi]

And yes, while Tolkien began crafting his private mythology early in his life, his fully interwoven legendarium only coalesced during and after writing The Lord of the Rings, drawing on many influences. Works that also influenced Eddison included but are not limited to: Motte-Fouqué’s The Magic Ring, Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen, and the Finnish Kalevala. But unlike Tolkien, Eddison was first at creating an enclosed world with its own history and cultures which were not pseudo-historical pastiche. Michael Rogers, writing a short review for Library Journal, repeated Tolkien’s genuine praise for Eddison as a peer in world-building.[vii]

The Truest Special Effect: Heroic Language

Forget CGI-infested fantasy film and tv— Eddison’s archaic, ornate prose is fantasy’s ultimate special effect. Carlo Rotella, writing in The New York Times Magazine, celebrated this elevated language as more immersive than any cinematic spectacle.[viii] Ursula K. Le Guin, in her 1973 essay “From Elfland to Poughkeepsie”, called Eddison’s pseudo-Shakespearean, KJV-inflected style the “Elfland accent”. Describing Elfland-ish as voice so mythic it creates the very air of another world. To her, the most powerful force in fantasy storytelling is style: “style isn’t extra; it’s everything.”[ix]

Larson, Young, and Le Guin agree Eddison’s elaborate sentences aren’t affectations but a carefully crafted voice essential to sustaining his mythic vision. This elevated style, challenging though it may be for modern readers, gives Eddison’s world its moral complexity: from the noble but flawed Demons to the villainous yet courageous King Gorice XII, and Gro. Oh, Gro! The conflicted counselor who becomes the novel’s most psychologically rich character, reflecting the disillusionment of a post-Great War world.

The Fear of Death and a Universe Enclosed

Bryan Attebery, in Fantasy: How It Works, suggests the endless battles of The Worm Ouroboros embody a defiance of death itself, a refusal to surrender to mortality.[x] Joseph Young, again writing in Extrapolation, explains Eddison conceived this cyclical struggle in childhood, revealing a lifelong obsession with eternal heroism. In Eddison’s world, to be heroic is to strive beyond death, but heroism is also tinged with cynicism. The novel’s ouroboros ending, where victory dissolves into emptiness and war begins anew, becomes a radical meditation on beauty, glory, and the terror of mortality.

As readers might conclude: “Victory is an illusion when the war never ends.”

For some readers, the ouroboros ending is maddening. But Larson argues this eternal return is the point: it embodies both the futility and the thrill of endless conflict. Young explored in his own work how Eddison had obsessed over the looping narrative of death and rebirth since boyhood, proving the ouroboros isn’t a gimmick but the beating heart of his myth. Le Guin adds Eddison’s towering prose sustains such a mythic exploration of life and death. Without his grand language the cycle of war and glory, the ordinate to the life and death abscissa, would collapse into triviality.

From Stephens and Barr to Attebery, Young, Stableford, Rotella, Larson, and Le Guin, the critical consensus is clear: The Worm Ouroboros isn’t a medievalist curiosity. It’s a lifelong dream realized in prose, a fearless exploration of courage, beauty, and death.

Final Verdict: Read If You Dare

The Worm Ouroboros isn’t easy. Its archaic, elevated voice demands patience and a taste for the poetic. But if you crave a fantasy that challenges you as much as it dazzles, this is your next obsession. More than an homage to medieval romance, it’s the purest realization of a child’s heroic dream. It’s an uncompromising testament to the power of imagination and the eternal allure of struggle.

Because in Eddison’s world, as Le Guin reminds us, “every word creates the world itself;” and The Worm Ouroboros proves that, with the right voice, a story can become immortal.

Citations

[i] James Stephens, “Introduction to The Worm Ouroboros,” originally published in The Irish Statesman, 1924; reprinted in The Green Book, Issue 8, Swan River Press, 2016.

[ii] Donald Barr, “A Place of Ought-to-Be,” The New York Times Book Review, Dec. 28, 1952.

[iii] J.R.R. Tolkien, “Letter 199,” in The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien: Revised and Expanded Edition, HarperCollins, 2023 [orig. 1981], ISBN 978-0-00-862876-5.

[iv] Brian Stableford, “The Worm Ouroboros,” Survey of Modern Fantasy Literature, vol. 5, May 1983.

[v] Eugene Larson, “The Worm Ouroboros,” in Paul Di Filippo, ed., Critical Survey of Science Fiction and Fantasy Literature, 3rd ed., vol. 3, pp. 1360–1362, Salem Press, 2017, ISBN 978-1-68217-284-1.

[vi] Joseph Young, “The Foundations of E.R. Eddison’s The Worm Ouroboros,” Extrapolation, vol. 54, no. 2, 2013.

[vii] Michael Rogers, review of The Worm Ouroboros, Library Journal, vol. 116, no. 10, 1991.

[viii] Carlo Rotella, “‘The Worm Ouroboros’,” The New York Times Magazine, Jan. 8, 2023.

[ix] Ursula K. Le Guin, The Language of the Night, Scribner, 2024 [orig. 1992], includes the essay “From Elfland to Poughkeepsie” (1973), ISBN 978-1-6680-3490-3.

[x] Bryan Attebery, Fantasy: How It Works, Oxford University Press, 2022, ISBN 978-0-19-285623-4.

By Alexander Olivarez

NEXT: Science Fiction Author John Scalzi Closes Out Pride Month By Mocking God's Promise To Mankind

I haven't read this book. It sounds interesting.